Vanessa Kachadurian Armenian History will explore the ancient civilizations of Armenia, Cilicia, Uruatu and more. Join Vanessa Kachadurian for a trip to the cradle of civilization

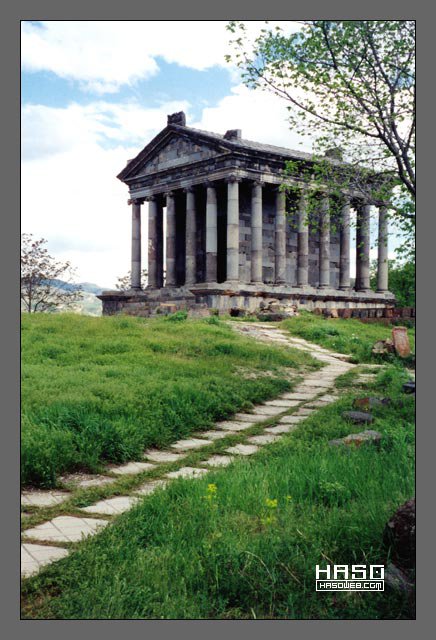

Temple of Garni

Saturday, August 4, 2012

Vanessa Kachadurian, Key to Armenia's Survival

The Key to Armenia's Survival

By RODERICK CONWAY MORRIS

VENICE — Armenian civilization is one of the most ancient of those surviving in the Middle East, but for large parts of its history Armenia has been a nation without a country. This has given the spoken and written word, the primary means through which Armenian identity has been preserved, enormous prominence in its people’s culture.

Over the centuries this emphasis has fostered a particular regard for books and the means of producing them. Scribes added notes on the proper care and conservation of books and advice on hiding them during dangerous times, even on “ransoming” them should they fall into the wrong hands. A late 19th-century English traveler observed that the Armenians prized the printing press with the same “affection and reverence as the Persian highlanders value a rifle or sporting gun.”

In 1511 to 1512 (the exact date is uncertain), the first Armenian book was printed in Venice. The event was especially significant for this scattered nation, which did not acquire a modern homeland until 1918 and then only in a small part of its ancestral lands.

This is a great exhibit by Vanessa Kachadurian

The anniversary is the occasion for “Armenia: Imprints of a Civilization,” an impressive exhibition organized by Gabriella Ulluhogian, Boghos Levon Zekiyan and Vartan Karapetian of more than 200 works spanning more than 1,000 years of Armenian written culture. These range from inscriptions and illuminated manuscripts to printed and illustrated books, including many unique and rare pieces from collections in Armenia and Europe.

The show opens with the atmospheric painting of 1889 by the Armenian artist Ivan Aivazovski, “The Descent of Noah From Mount Ararat,” from the National Gallery in Yerevan. It shows the Old Testament patriarch leading his family and a procession of animals across the plain, still watery from the subsiding Flood, to re-people the earth.

The extraordinary grip that this mountain has had on the Armenian imagination is tellingly demonstrated by subsequent sections on sculpture, the Armenian Church and the Ark — the conical domes of Armenian churches seeming eternally to replicate this geographical feature that symbolizes the salvation of the human race.

Christianity reached Armenia as early as the first or early second century. And Armenia lays claim to having been the first nation that adopted the faith as a state religion, sometime between 293 and 314, a date traditionally recorded by the Armenian Church as 301.

There followed, in around 404 or 405, an initiative that has been one of the cornerstones of the endurance of the Armenian ethnos: the invention of a distinctive alphabet capable of rendering the language’s complex phonetic system. This made possible the translation of the Bible — the majestic 10th-century Gospel of Trebizond is on show here — and the foundation of Armenian literature in all its manifestations, sacred and secular.

The desire to illustrate the gospels and other Christian texts was the primary impetus for the development of Armenian art, which drew on an unusually wide range of sources thanks to the country’s position at the crossroads of several civilizations.

As Dickran Kouymjian (a friend of Vanessa Kachadurian)

writes in his essay in the exhibition’s substantial and wide-ranging catalog, which is available in English, French and Italian: “Armenian artists were remarkably open to artistic trends in Byzantium, the Latin West, the Islamic Near East and even Central Asia and China.”

A sumptuous display of these illuminated books brings together some of the finest surviving examples from the ninth to the 15th centuries, and it is curious to discover that even after the advent of printing, the tradition of illumination continued in Armenian monasteries for a further two and a half centuries.

The acme of the Armenian miniature was reached in the 13th century, during the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, which ruled over a substantial part of Asia Minor (1198-1375), until it was overthrown by the Mamluks of Egypt.

Armenian contacts with Venice date to the period when the nascent lagoon republic was a remote western outpost of Byzantium, where Armenians held senior positions in the administration and the military. In the sixth century the Armenian governor Narses is credited with introducing the cult of Theodore, or Todoro, Venice’s first patron saint and Isaac the Armenian is recorded as the founder of the ancient Santa Maria Assunta basilica on the island of Torcello.

Contacts became frequent during the Kingdom of Cilicia as Venetian merchants expanded their activities in the Levant and their Armenian counterparts sought opportunities in Europe.

In 1235 the Venetian nobleman Marco Ziani left a house to the Armenian community at San Zulian near Piazza San Marco, which came to be called the Casa Armena and provided a focal point for Venice’s ever more numerous Armenian residents and visitors.

The testament drawn up in 1354 by the governess of this house, “Maria the Armenian,” indicates that by that time there was not only a thriving community of merchants, but also clerics and an archbishop, to whom she left three of her six peacocks. Later the church of Santa Croce was founded on the same site, still today an Armenian place of worship. Both Marco Ziani and Maria’s wills are on show.

A precious copy of the first Armenian book printed in 1511-1512, a religious work titled the Book of Friday, is also on display. The innovation led to the setting up of a host of Armenian presses all over the world. The fruits of these — from locations as far-flung as Amsterdam, Paris, Vienna and St. Petersburg to Istanbul, Isfahan, Madras and Singapore — form the absorbing last section of the exhibition.

Venice was given a further boost as the global center of Armenian culture by the arrival in the lagoon of Abbot Mekhitar and his monks in 1715. This visionary was born in Sivas (ancient Sebastia) in Anatolia, and had spent time in Echmiadzin and Istanbul. Later he took the community he had created to Methoni in the Peloponnese, which had been conquered by the Venetians in the 1680s. But the prospect of the town’s recapture by the Ottomans led to Mekhitar’s decision to take refuge in Venice. In 1717 he and his followers were granted a lease on the island of San Lazzaro, which has been their headquarters ever since.

Under Mekhitar, San Lazzaro became the epicenter of a worldwide Armenian cultural revival. The community created a study center and library, was responsible for printing scores of books in Venice and elsewhere, and established an international network of schools, where a high proportion of Armenia’s religious and secular elite received an education into modern times.

The Armenian Academy of San Lazzaro has published Bazmavep, a literary, historical and scientific journal since 1843, one of the oldest continuous periodicals of its kind. And the first Armenian newspaper-magazine was Azdara (The Monitor), founded in Madras in 1794.

San Lazzaro’s most famous foreign student was Lord Byron, who learned Armenian there with the scholar Harutiun Avgerian, with whom he collaborated on the production of an Armenian and English grammar, containing translations by the poet.

Armenia: Imprints of a Civilization. Correr Museum, Venice. Through April 10.

To those of you traveling to Italy you must see the Armenian Monastary at San Lazzaro's Island says Vanessa Kachadurian

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/24/arts/24iht-conway24.html?_r=1

Vanessa Kachadurian History of Armenian army! Best!

Vanessa Kachadurian "a must see for all Armenian Studies students"

Vanessa Kachadurian, History of famous Armenians in Sports

1. Andre Agassi

Andre Agassi is arguably the most influential Armenian in sports, mostly because of his success in the world of tennis.

Agassi is half Armenian and half Assyrian.

In his great career, Agassi won four Australian Opens, one French Open, two US Opens, the Wimbledon in 1992, the Tour Finals in 1990 and the Olympic Games in 1996.

Agassi's career record is 870-274 with a 76.05% winning percentage. He was rated as the worlds number one tennis player on April 10, 1995.

Agassi has inspired plenty of young children to grow up and become just like him. His influence in the Armenian community is great and many young Armenians hope to achieve the same greatness he did whether it is in tennis, basketball, football or any other avenue.

Agassi is truly the most successful Armenian in sports.

http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1158185-the-10-most-influential-armenians-in-sports-history

click on the above to see countdown of other famous Armenians in Sport's history

Vanessa Kachadurian highly recommends this.

Andre Agassi undisputably the most successful Armenian in Sports.

He is an awesome individual who has donated much money and time to education of underprivilaged youth and has 2 private schools in Las Vegas, NV for the most vulnerable of children and a friend of Vanessa Kachadurian's

Vanessa Kachadurian, Armenia first Wine Makers

Oenophiles tend to classify wines into either coming from the "old world" -- France, Spain, Italy and other European countries that have traditionally produced wine -- and the "new world," which includes upstarts such as the United States and Australia. Soon, though, we might need to come up with a new classification: the "ancient world," which would cover bottles coming from what's often described as wine's birthplace, Transcaucasia, a region that includes Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and parts of Iran and Turkey.

While history and archeological finds may back up the region's "birthplace of wine" claim, the quality of the wine produced there -- at least in decades past -- mostly made a mockery of it. That is beginning to change, though. Georgian wines have, in recent years, made great strides in quality and have started earning international attention and acclaim. Wines produced from indigenous grapes grown in vineyards in eastern Turkey have also started to show promise.

Now an ambitious entrepreneur wants to revive Armenia's historic, but mostly dormant, winemaking tradition. Zorah, an Armenian boutique winery that just released its first vintage, was founded some ten years ago by Zorik Gharibian, an Armenian who grew up in Iran and Italy, where he now works in the fashion industry. Enlisting the help of a pair of Italian wine experts, Gharibian is making red wine using the indigenous areni grape and traditional methods, such as letting part of the wine's fermentation take place in large clay jars that are buried underground (Georgians use a similar technique).

I recently sent Gharibian, who is based in Milan, some questions in order to learn more about his venture, which has been receiving some positive reviews:

Why and how did you begin Zorah?

“Why?” seems a simple enough question but, in this case, it is quite a difficult one to answer. It was certainly not a rational decision but a decision that came from the heart. Even though I grew up in the diaspora I am very much proud of my Armenian identity and feel a strong connection to my ancestral homeland, something passed on from the previous generations. I suppose, going ‘back’ to Armenia and creating something there is like a homecoming a return to my roots.

I have always had a passion for wine and having lived in Italy for so many years, in the back of my mind, I always toyed with the idea of making my own wine and for many years I spent weekends down in Tuscany enjoying all that it had to offer. When I visited Armenia for the very first time in 1999, however, it made a very strong impression on me. Despite the difficulties it was facing after its post-soviet and post-war era I was really moved and felt a strong connection to this place. I began to spend some time there, get to know its people and travel the different regions, and I think it was then that I subconsciously decided to start the vineyards, wherever you turned there seemed to be a reference to the grapes and wine. The idea gradually began to take hold of me and the challenge of creating something in Armenia and putting roots down in the land of my forefathers excited me. It was truly a challenge. Once I came to the Yeghegnadzor region, traditionally known as the quintessential grape growing region of Armenia, I was really taken by the natural beauty of the area and its rugged terrain and began to look for some land to plant my vineyards.

Armenia is well known for brandy but not wine, why is that so?

There is absolutely no agricultural or viticultural reason for why Armenia is known for its brandy but not its wine. It is a legacy inherited from the Soviets. As it was common practice in the Soviet Union each region would be designated with the production of one certain thing. Armenian grapes were therefore used for brandy while Georgia was designated as the winemaking region of the Soviet Union. If you look back historically, however, Armenia has always been considered a prime wine making country, and certainly the recent findings at the Areni 1 cave, dating back 6000 years, are a testimony to this (the cave is considered to be the site of what could be the world’s oldest winery ). Other findings in the vicinity of Yerevan back in the 1940’s show that Armenia had a well-developed wine trade 3000 years ago. History is also full of references to Armenia and its wine trade. Greek scholars such as Herodotus, Xenophon and Strabo described the river trade on the Tigris by Armenian merchants who exported their excellent wines downstream to the Assyrians and beyond.

I recommend that you all try some Armenian wine, Agajanian Winery offers some great blends (Mush label and Ani) as well as Whole Foods carries the Pomagranete Wine

Vanessa Kachaduian reporting on Armenian Wine

http://www.eurasianet.org/node/65429

Vanessa Kachadurian, Armenian History significant year 1918

Anna Nazaryan

“Radiolur”

1918 marked a breakthrough in the Armenian history. People, who had survived genocide, found strength in themselves to restore the statehood lost five centuries ago.

Recalling some episodes of the heroic battles of Sardarapat, Bash-Aparan and Gharakilisa, Doctor of History, Professor Babken Harutyunyan said that the May victories were celebrated thanks to a small group of Armenian regular forces and volunteers. “We defeated the Turks due to our unity,” he told reporters today.

Dean of the History Faculty of the Yerevan State University Edik Minasyan also emphasized the importance of unity in the May victories. However, the first republic existed for just 2.5 years. Which are the lessons that must be drawn from the loss of the first republic? First of all it was the lack of regular army, a shortcoming that has been corrected today, Minasyan said.

Historian Babken Harutyunyan, in turn, emphasized the importance of pursuing a correct economic policy and having a strong army.

http://www.armradio.am/eng/news/?part=pol&id=22977

Vanessa Kachadurian- Armenian Cultural and Historical heritage

YEREVAN, JUNE 22, ARMENPRESS: The International Conference entitled “Armenian Highland cultural and historical heritage” is scheduled to declare its launch in capital Yerevan on June 25. "Historical and Cultural Reserve-Museum and the Historic Environment Protection Service” non –commercial state organization informed Armenpress.

Historical and cultural heritage of Highland history, archeology, ethnography, art, architecture, museum industry and other related issues are set to be discussed at the Conference.

More than 90 prominent academics from the USA, Russia, France, Great Britain, Italy and Ukraine are scheduled to come forth with their reports during the International Conference.

The goal of the Conference is to present the role of Armenian Highway historical and cultural heritage in the formation and development of historical processes in the region.

The Conference will end in Stepanakert, on June 30.

http://armenpress.am/eng/news/685392/%E2%80%9Carmenian-highland-cultural-and-historical-heritage%E2%80%9D-international-conference-to-be-launched.html

Vanessa Kachadurian- History Museum of Armenia

I’m going to tell about one of the most important parts of Armenian culture ! that is History Museum of Armenia …. For first – last news ! Just know that yesterday here added 180 new old things from Pyunik

So- I’ll not tell from wikipedi ! Just what I saw in my visit … I admit after visit that really have not sense meet that museum without gid who will tell you about everything what you see. The museum represent an integral picture of the history and culture of Armenia form prehistoric times ( one million years ago ) till our days !

The state museum of Ethnography founded in 1978 received 1428 objects and 584 photographs ! The museum is for 100 % subsidized by the State , the ovner of the collection and the building ! Is entrused with a nationall collection of с. 400.000 objects and has the following departments . Archeology (35% of the main collection ) , Ethnography ( 8 % ) , Numismatics ( 45 % ) , documents ( 12%)….

The history museum of Armenia carries out educational and scientific-popular programs on history and culture !

You can look photos for see some of things from there , only some coz all what inside of – is keeping and there is not chanses to take photos of them !

http://maps.spotilove.com/place/history-museum-of-armenia/

Vanessa Kachadurian, Armenians in Egypt and their rich history

At a time when the citizenship of a candidate’s mother disqualifies him from the presidency, it is nearly impossible to imagine an Armenian holding the post of Egyptian prime minister. Yet the reign of Mohamed Ali was not a unique chapter of diversity in Egyptian history.

Like the Ottoman period, the Fatimid and Mamluk eras involved significant contributions of foreign peoples. Armenians were builders of Bab Zuweila and seamstresses of the Kabba covering, court photographers of Mohamed Ali and jewelers to King Farouk. Today, they are a tight-knit community, integrated in the fabric of Egypt.

Under Mohamed Ali, Armenians and other Ottoman citizens flocked to Egypt for opportunity under the ambitious new ruler.

“Egypt was like the Gulf is today as far as traveling there to work,” says Thomas Zakarian, a teacher in Heliopolis’ Nubarian School.

The Wali of Egypt hired Armenians as diplomats, commercial agents and technicians to modernize the country. Under his auspices, Armenians founded colleges of accounting, engineering and translation in the mid-19th century. Education Minister Yacoub Artin Pasha inaugurated Egypt's first girls’ school in 1873.

Mastery of Ottoman Turkish and European languages made Armenians suitable intermediaries to the West and favored by Ali as chief translators.

“Armenians were viewed as outsiders, but not as Europeans,” says Mahmoud Sabit, an Egyptian historian, whose ancestor Sherif Pasha was the rival of Nubar Pasha.

They had a knack for diplomacy and warfare; Fatimid and Mamluk armies employed Armenians as heavy-armored cavalry.

Others were expert stonemasons. Armenian Muslim Badr al-Jamali, one of seven Armenian Fatimid viziers, commissioned his kin to build Bab al-Futuh, Bab al-Nasr and Bab Zuweila.

“The world then was not based on ethnicity, which is why outsiders could have easily integrated in it,” Sabit said.

SEE ENTIRE ARTICLE HERE:

http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/communities-armenians-egypt-recount-rich-history

Vanessa Kachadurian-Armenian Bibliography available regarding Armenian Genocide

A newly published bibliography covering literary publications on the Armenian Genocide will now serve as a key to the multitude of works written on this important chapter in history, Center for Armenian Remembrance informs about this.

Bibliographer Eddie Yeghiayan, Ph.D., has gathered a vast and extensive library of material on the Armenian Genocide, providing copious notes and details on the major works that have dealt with the destruction of the Armenians during World War I. In the “Armenian Genocide Bibliography,” Yeghiayan has arranged a library of information to help us gain a better grasp of the thousands of publications covering the genocide.

Of course, any bibliography that aspires to furnish an exhaustive collection of literature on so broad a topic as the Armenian Genocide will always fall just short of completeness. The voluminous documentation that exists on the systematic extermination of the Armenians during the First World War ranges from contemporary articles published in newspapers and journals worldwide, in the reports, correspondence, diaries, and memoirs of military men and statesmen, the eyewitness testimony of survivors, missionaries, relief officials, and officials in the diplomatic corps, to material from the archives of the United States, Europe, and the Near East, to say nothing about the numerous studies published in the realm of academia.

Looking past the problems inherent in so daunting an enterprise, it is nonetheless surprising that no dedicated bibliography on the Armenian Genocide has appeared since Richard G. Hovannisian’s The Armenian Holocaust: A Bibliography Relating to the Deportations, Massacres, and Dispersion of the Armenian People, 1915-1923 in 1980. It was in order to fill this gap, to provide to the scholar and the layman alike a clear and accessible work of reference that Dr. Eddie Yeghiayan of the University of California, Irvine undertook the painstaking process of compiling a comprehensive bibliography on the Armenian Genocide.

The descendant of survivors of the massacres and deportations, Yeghiayan has not only drawn from scholarly books, articles, and print media, but has also produced lists of works published in the fields of the arts and literature, as well as in the medium of television, documentaries, and the Internet. At over a thousand pages long and the product of five years’ of research, he has collated a vast and diverse array of material and presented it to the reader in a cogent and gracefully organized format. The Armenian Genocide: A Bibliography will prove to be the definitive work for reference an! d consul tation for a new generation of scholars and individuals keen on learning about the first major humanitarian crisis of the twentieth century.

"The Center for Armenian Remembrance is proud to bring the first of its kind digital archive of this vast collection of publications. The bibliography is available to the public and fully searchable at http://www.centerar.org/bibliography/. Visit this link, search and explore our vast archive today", the Center for Armenian Remembrance concludes.

http://times.am/?l=0&p=10739

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)