The Armenian Genocide - Next Edition!

By Miljan Peter Ilich

In the 1870s the rulers of the Ottoman Empire embarked on a policy designed to ruthlessly eliminate the bulk of its Armenian population. For over 40 years they and their successors sought with great determination to achieve that goal whenever possible. In doing so, they carried out periodic genocidal killings that dwarfed all ethnically based exterminations up to that time. This was a series of genocides rather than just the one more widely known genocide.

The genocidal policy of Turkish leaders towards Armenians inspired Adolf Hitler to plan his own holocaust. In a 1931 interview only published in 1968, Hitler said:

“Everywhere people are awaiting a new world order. We intend to introduce a great resettlement policy… Think of the biblical deportations and the massacres of the Middle Ages… and remember the exterminations of the Armenians.” Hitler stated that he had to protect “German blood from contamination, not only of the Jewish but also of the Armenian blood.”

In 1939, on the eve of World War II, Adolf Hitler urged his leading generals to be ruthless in the coming conflict just like the Turks were in their Armenian genocides, saying famously, “Who, after all, is today speaking of the destruction of the Armenians?” Hitler believed that the world does not care about the brutality of means used as long as they are successful in the end. This also is a lesson he drew from the Armenian tragedy.

We must remember history to learn a different lesson than Hitler did. We have to ardently work to use history as a learning experience to avoid the mistakes and terrors of the past. If we do not, we will experience unthinkable horrors again and again. Perhaps the Copts of Egypt or other such minorities may then be the Armenian victims of the future.

Of course, historical memory is also needed to honor the victims. Let us memorialize those who suffered rather than those who destroyed the innocent. However, this recollection should not lead us to revenge, but rather to learning and greater understanding.

Who are the Armenians?

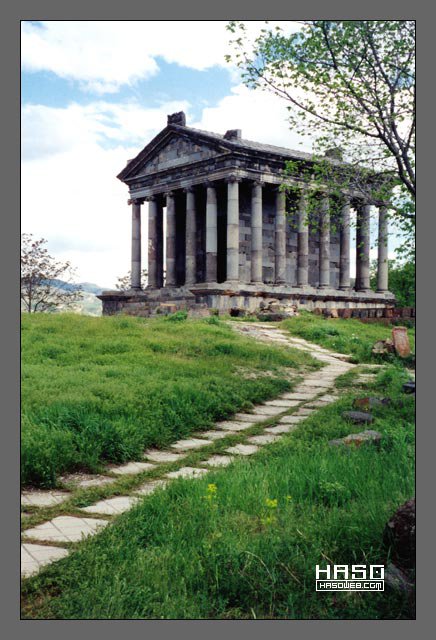

Armenians are an ancient people whose history goes back about 3,000 years. Their first rise to historical importance was in the Kingdom of Urartu in the ninth and eighth centuries before Christ. Urartu stretched from the Caucasus to the Euphrates River, covering a vast expanse.

Under King Tigranes from 95 to 55 B.C., Armenia was a huge empire that dominated much of the Middle East from the Caucasus to the borders of Egypt and east to Syria and Persia. It became a center of Hellenistic culture and a major challenger to the Roman Empire.

Though the Romans eventually conquered Armenia, they had such respect for it that for centuries they allowed self-rule under its own kings as a Roman ally. About 300 A.D. Armenia was the first country to officially adopt Christianity. Emperor Constantine, the first Christian ruler of Rome, became its staunch friend.

Armenians became a crucial part of the Byzantine Empire. As such, they contributed greatly to iconography and religious architecture. They also continued to develop a strong literary and poetic tradition.

By the early 1400s, the Ottoman Turks conquered most of Armenia. Armenians were placed in the conquered Christian category subordinate to Muslim rulers. They had religious rights as long as they paid the special infidel tax, but they had no political rights. Despite major discrimination, many of the people prospered in commerce and industry. They held fast to their Christian Armenian identity and would not become Muslim Turks. By the 1870s there were at least three or four million Armenians divided between Russia and Turkey.

In modern times Armenians outside of Turkey have excelled in the arts. Composers like Khachaturian in Russia and Hovhaness in America became famous by using some Armenian traditional musical motifs in their compositions. William Saroyan became one of the greatest American dramatists. Many other Armenians in the Diaspora prospered in a variety of fields. What happened to Armenians in Turkey was very different. It is the subject of these articles.

The Forgotten Genocide - Part I

The first phases of the Armenian genocides took place in the second half of the nineteenth century. Though shockingly brutal in their execution, they have been largely forgotten even by some Armenians. What took place in this period was not only horrifying in itself, but set the stage for the even greater horrors that followed.

The martyrdom of Armenians was largely the result of the policies promoted by a new ruler. In 1876 Sultan Abdul Hamid II ascended the throne of the Ottoman Empire. He was young and energetic, but the empire he ruled was old and collapsing with many of its nationalities like the Greeks, Serbs and others obtaining independence for a large portion of their ethnic groups. The most populous Christian ethnicity left within the Ottoman Empire proper were the Armenians with an estimated population of about 2,000,000. They were an ancient people with a civilization that had flourished for thousands of years. In contrast, the Ottoman Turks had only arrived in what is now Turkey in the thirteenth century.

Sultan Abdul Hamid came to believe that his predecessors had been too generous in allowing the continued existence of major Christian populations in their realm. That is why the Greeks, Serbs and others had been able to gather enough strength to successfully revolt. He was certain that, in due course, Armenians would follow their example. Most Armenians had, until the 1870s desired nothing more than fair treatment as Ottoman citizens. However, that did not dissuade the Sultan from perceiving them as the enemy within. Though there was no evidence of major revolutionary Armenian movements, there were isolated instances of anti-Ottoman violence and several Armenian political groups advocated greater autonomy. The Sultan decided to preempt an Armenian uprising by increasing the hardships of their lives in his realm. Abdul Hamid’s long time friend Arminius Varnberry wrote that the ruler “had decided that the only way to eliminate the Armenian question was to eliminate the Armenians themselves.”

Varnberry’s conclusion was shared by United States Ambassador to Turkey, Henry Morgenthau, who was extremely knowledgeable with regard to the Sultan’s policies. He wrote that “Abdul Hamid apparently thought that there was only one way of ridding Turkey of the Armenian problem and that was to rid her of the Armenians. The physical destruction of 2,000,000 men, women and children by massacres organized and directed by the state, seemed to be the one sure way of forestalling the further disruption of the Turkish Empire.” This was by definition a plan for the first modern genocide.

For the first time in the modern age, an entire people were marked for destruction only due to their faith and ethnicity. Once that goal was set, its implementation was not long in coming. The Ottoman state attempted to generally eliminate the Armenian people from Turkey either by persuading them to leave or by an ultimate policy of extermination. The fact that the hard working and commercially inclined Armenians were generally more prosperous than the Turks made it easier for the Sultan to get considerable popular support for his anti-Armenian jihad. Greed and jealously have often motivated ethnic hatreds and they were strongly inflamed by the despotic ruler soon after taking the Turkish throne.

A first step taken to persecute Armenians took place when Abdul Hamid greatly raised the tax burden specifically on them. Those who could or would not pay were savagely punished. More violent measures soon followed. In 1876 and 1877, while Turkey was engaged in war with Russia, the Armenian quarter of Constantinople was burned and looted by the police and imperial soldiers. Many Armenians were slaughtered in the imperial capital.

Large scale killings of Armenians also took place near the city of Erzurum. Massacres spread to other areas. The German newspaper National Zeitung wrote: “It is clear that had the war continued in this fashion under these conditions, the Christian population of Turkish Armenia would have been exterminated in less than a year.” Captain Stokvitch, a Russian officer, reported that “children and adults were being thrown into flames and the cries of these unhappy victims, especially women, were heartrending. The streets of Beyazid were strewn with decapitated and mutilated corpses.” Men were often smeared with wax and naphtha and set on fire.

Western powers, hearing of the atrocities, protested and threatened intervention. Consequently the Sultan, who had both promoted and allowed the atrocities, backed down after many thousands of Armenians had been killed. He promised reforms. The attacks on Armenians decreased dramatically for a number of years. However, harassment and killings did continue at a low intensity.

By the final decade of the nineteenth century, Armenians, encouraged by the liberation of other Ottoman subject nationalities, were more vigorously organizing for greater rights and political protections. Sultan Hamid’s promises for reforms had proven to a large degree illusory and Armenians sought to make them real.

In 1894, the region of Sasun, which had a large Armenian population, but was dominated by Kurds, exploded into extreme violence when the Armenians were forced to pay tribute to local Kurdish chiefs as well as Ottoman taxes. They were unable to pay this double taxation. Turkish troops were called in and together with Kurdish militias engaged in an orgy of massive killings. British historian, Lord Kinross, described what was done to local Armenians: “The soldiers pursued them throughout the length and breadth of the region, hunting them like wild beasts up the valleys and into the mountains, respecting no surrender, bayoneting the men to death, raping the women, dashing their children against the rocks, burning to ashes the villages from which they had fled.”

An 1895 demonstration of Armenians in Istanbul to petition the Sultan for their rights was crushed by police. Many demonstrators were clubbed to death on the spot. Fanatical Muslims were allowed to rampage through the city, slaughtering Armenians like animals. The terror spread though the empire. Armenians were often given the choice of converting to Islam or death and many did choose to become Muslim to save the lives of their families.

British Ambassador Currie reported that due to “forced conversions… there are absolutely no Christians left” in Aleppo province in Ottoman Syria. Many thousands were forcibly converted in other areas. 645 churches and monasteries were destroyed and 328 churches were turned into mosques.

Large numbers of Armenians would not convert but died for their faith. Though the killings spread throughout Armenian populated sections of the empire, the worst massacres took place in the city of Urfa, which had been known as the ancient capital of Edessa. In December, 1895, Armenians made up about one third of the population. Turkish troops and mobs rampaged through the Armenian quarter, plundered their homes, killing all males over a certain age. A large group of young Armenian men were brought before a Sheikh who recited verses from the Koran while he slit the throats of the bound men like sheep. The Turks were not finished however.

Thousands had taken refuge in the local Cathedral. On a Sunday, Islamic mobs stormed the Church. Some cried out to the frightened Armenians to call on Christ to prove that he is greater than Mohammed. Then they set the Cathedral on fire. About 3,000 women and children were burned alive. Lord Kinross wrote that the total of Armenian dead in Urfa was 8,000.

Some Armenians resisted out of utter desperation. At Zeitoun, insurgents killed thousands of Turkish troops in bitter clashes. Though rare and isolated, the armed resistance was used by the Ottomans as an excuse for even greater massacres of innocents.

News of the genocidal slaughter spread to the West and the United States. The New York Times carried headline stories calling this an “Armenian Holocaust.” However, public opinion in America was mainly galvanized by the energy and devotion to the Armenian cause of two women in their seventies. Julia Ward Howe, author of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, was perhaps the most eloquent American voice condemning the Turkish atrocities, and trying to obtain help for Armenians. Though seventy six years old, she was full of energy for the Armenian cause. On November 26, 1894 at Boston’s historic Faneuil Hall, the first major American protest meeting regarding the issue took place and she gave an impassioned speech on the victimization of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. In stirring words she declared:

"I throw down the glove which challenges the Turkish Government to its dread account. What have we for us in this contest? The spirit of civilization, the sense of Christendom, the heart of humanity. All of these plead for justice, all cry out against barbarous warfare of which the victims are helpless men, tender women and children. We invoke here the higher power of humanity against the rude instincts in which the brute element survives and rules.”

Julia Ward Howe made many more appearances in the Armenian cause. Being a national icon, her influence was incalculable. She played a critical role in orchestrating American support for Armenians.

Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross, was particularly prominent in the effort to help Armenians. At seventy four years of age, she led the relief effort for Armenia and addressed mass meetings protesting the massacres. In January 1896 she personally escorted an American Red Cross aid mission to Istanbul. Clara Barton faced down the Turkish foreign minister Tewfik Pasha to obtain permission for the Red Cross to assist the suffering Armenians. Then she remained there to supervise the start of the relief effort.

Western powers, affected deeply by the horrified public opinion in their countries, were moved to take steps to try to stop the slaughter. Diplomatic measures to persuade the Turkish government to cease and desist were tried first. Former British Prime Minister Gladstone pushed for British military intervention. European and even some American naval forces sailed towards the Ottoman Empire. Intervention by strong military forces was threatening unless Turkey’s rulers stopped the massacres. As U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau wrote, faced with this threat, Istanbul halted the slaughter. Meanwhile, some 200,000 Armenians had been brutally exterminated.

Turkey gave new guarantees for the protection of Armenians. These promises were partly kept at first, but not many years later were shown to be totally worthless. The Armenian national nightmare had only just begun. Even worse horrors were yet to be inflicted on the long suffering Armenian people.

About Miljan Peter Ilich

Historian and filmmaker, Miljan Peter Ilich has eight feature length films, many documentaries and a number of short subjects to his credit as Producer. Among them is the controversial ArtWatch, a collaboration with the late Professor James Beck of Columbia University, Frank Mason of the Art Students League of New York and director James Aviles Martin and TCI: the First Hundred Years commissioned by Technical Career Institutes.

Other documentary film credits include Chios 1822: Martyrdom and Resurrection of a People and Cyprus: the Glory and the Tragedy. Feature film credits include the cult film classic, I Was a Teenage Zombie, Mothers; Unsavory Characters; What Really Frightens You, Soft Money and the New York 3-D sensation, Run For Cover in 3-D.

Peter Ilich has also produced for theater and television in New York, most notably the acclaimed play Struck Down, about the 1994 Baseball season. He is the co-host, writer and co-producer of Orthodox Christian Television's Chios: the Island of Saints; Cyprus: the Glory and the Tragedy; The Sacred Land of Kosovo and frequent panelist on Democracy in Crisis.

Dr. Ilich is a Juris Doctor, New York University and PhD. City University of New York and is a Professor of Law at Technical Career Institutes in New York City.